Study finds big potential in local charter school’s residency program

by Kevin Forestieri – Staff Writer, Mountain View Voice

Jacklyn Kaiser, an associate teacher, helps a student with a reading assignment at Bullis Charter School. The school’s associate teacher program aims to improve teacher training and retention by offering new educators a supportive co-teaching program for their first year in the classroom.

When it comes to teaching, there are no training wheels. Newly certified teachers fresh out of school often go through a trial by fire, learning to manage a classroom of 30 or more kids, communicate with parents and line up a state-standardized curriculum spanning a 10-month school year.

The steep learning curve is blamed for a whole host of ills, from high teacher turnover rates to acting as a deterrent to entering the profession, leading some schools to create programs to help nascent teachers get a handle on their first year in the field. But a new study released last month found that California schools could take it one step further, allowing new teachers an entire year-long “residency” alongside experienced staff, learning the ropes.

The study, released last month by the Bank Street College of Education, took a close look at Bullis Charter School’s Associate Teacher program, which provides already-certified teachers with a full year of experience co-teaching in a classroom — sort of like a teacher aide with much greater responsibilities. The study found that the residency was not only effective at giving teachers the hands-on experience sorely missing from most teacher credential programs, it was entirely possible to replicate in schools and districts without breaking the bank.

Financial feasibility tends to be the biggest problem, said Brigid Fallon, a program analyst for Bank Street College. She said there are countless examples of residency-style programs for teacher undergraduates and certificated teachers out there, but the trouble is schools and districts rarely bake it into the annual budget as a years-long commitment. Most of them are funded as pilot programs or through short-term grants, and they simply disappear once the cash runs out.

“They are really successful, quality programs, and when those grant dollars die, they don’t know how to continue to support the model,” she said.

The study focusing on Bullis Charter School — part of a larger body of work dubbed the “Sustainable Funding Project” — uses the charter school’s Associate Teacher as a sort of proof of concept, that schools can pull off a long-term teacher training bridge that can act as both a pipeline for teacher hiring as well as a staffing boost in the classroom, meaning more one-on-one student support and lessons better tailored for diverse classrooms.

Sara Fernandez, a fifth-grade teacher at Bullis, called her year as an associate teacher an “amazing” opportunity full of direct teaching experience and immediate feedback from teachers across all three fifth-grade classrooms. There’s a whole different world of teaching that you aren’t prepared for when you come out of a teacher training program, she said.

“A lot of the time you throw in a teacher and it’s either sink or swim,” she said. “I didn’t realize how much it would help me until I was in it.”

After going through the Associate Teacher program, Fernandez said she directly transitioned to a homeroom teacher job at Bullis with great ease because she was already acclimatized to the school’s culture, families and classroom norms. Knowing which teachers to go for advice and the “ins and outs” of each school system has its own learning curve as well, she said, so she was able to direct 100 percent of her attention on students and teaching.

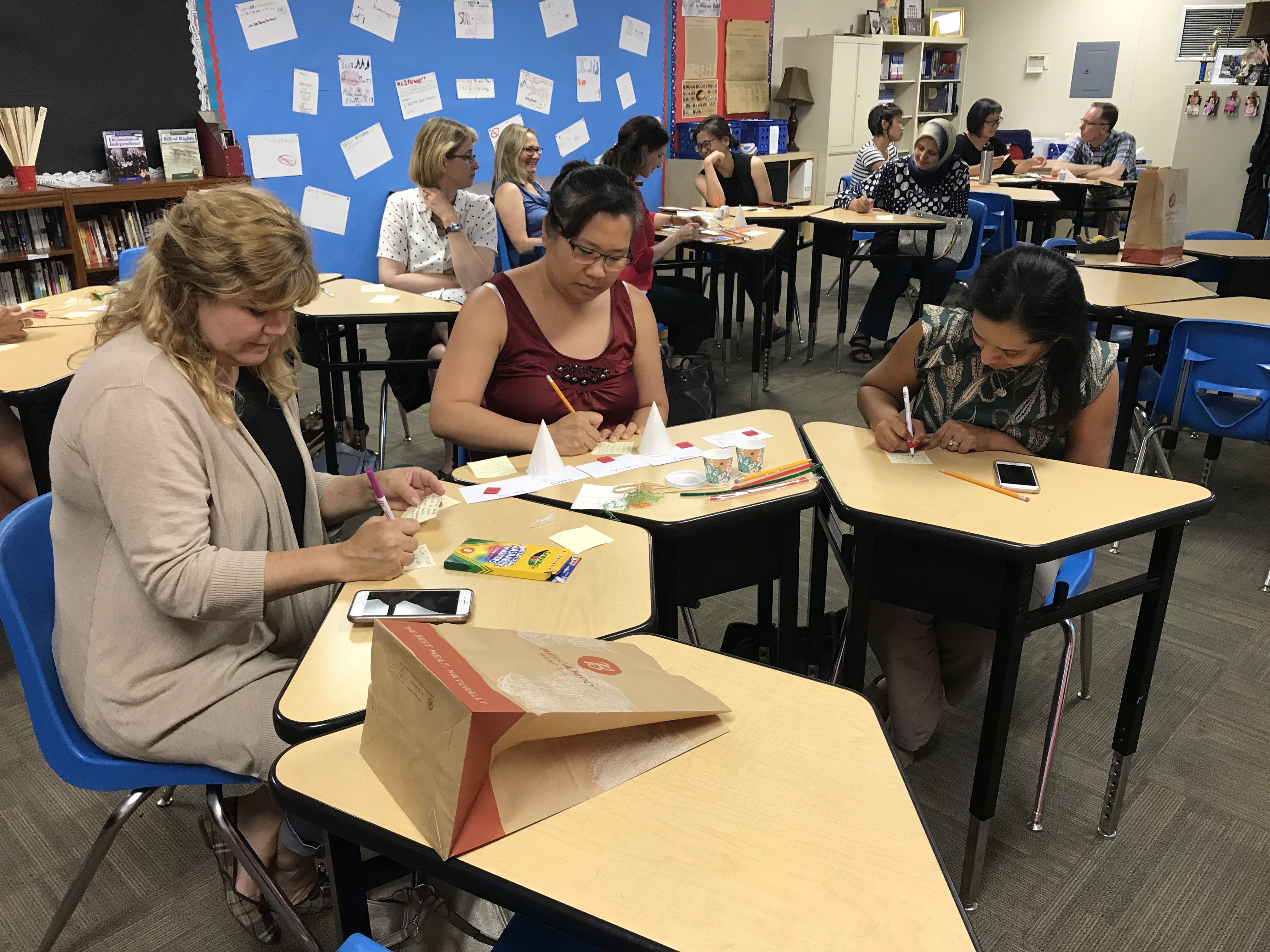

Jessica Morgan, an eighth-grade teacher at Bullis Charter School, says the associate teacher program effectively bridged the gap between getting her teaching credentials and joining the workforce.

Bullis teacher Jessica Morgan kicked off her tenure at the school nine years ago, serving a shorter six-month stint as an associate teacher before jumping into a full-time position. She said each grade level shares an associate teacher, and she has made it a priority to use those valuable two hours of bonus staffing as strategically as possible. Often times that meant breaking math lessons out into several groups, making sure students are understanding the material and not falling behind.

“We tag-team on supporting the kids in ways that really meet them where they’re at as individual students,” she said.

Back when she was an associate teacher, Morgan said the program was a little more experimental and looked different from one classroom to the next — the Associate Teacher program is more formally structured and has a designated “mentor” teacher — but she nevertheless found it an effective bridge between getting her credentials and joining the workforce as a classroom teacher.

“I will always tell everyone that, no matter how confident I felt leaving the credential program, I did not have the skills yet that I gained through our Associate Teacher program,” she said.

The downside to residency programs is that it can be pretty expensive, and often times its the aspiring teachers who are stuck carrying the burden. A 2016 study from the Sustainable Funding Project found that residency programs pay little to nothing, forcing the training teachers to seek out loans, extra jobs or rely on friends and relatives for support. The financial disincentives make residency programs a hard sell, making it difficult to justify and otherwise useful experience before full-time teaching.

But the study argues that there’s really no excuse — schools in California have the financial means to pay teacher residents if they so choose. Researchers created two hypothetical schools, one with students from high-income families like Bullis as well as a majority low-income school, and crunched the numbers using California’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) to see if it would be financially feasible to support one teacher resident per grade level at a school. The results found that in both cases, 1 percent or less of discretionary funding would need to be committed to the program.

Those modest figures may not pan out here in the Bay Area, however, because the study assumes teacher residents are paid an annual stipend of $15,000, roughly on par with annual income of employees making federal minimum wage. Fallon said the stipend represents a “midpoint” based on existing programs across the country, which range from no pay at all to just under a starting teacher salary, and that local schools and districts need to tailor their compensation based on the area’s cost of living. In the case of Bullis Charter School, associate teachers make anywhere from $36,750 to $47,300.

The study contends that having extra support staff through teacher residents can help to reduce costs elsewhere in the budget, making residency programs more feasible. Three-fourths of teacher absences are filled by associate teachers at Bullis, minimizing costs for substitute teachers, and the teacher residents often fill the role normally carried out by instructional aides in the classroom, meaning fewer classified staffers are needed in day-to-day classroom operations.

The other benefit is that teacher residents are far more likely to stay at the school once they get hired as full-time teachers, driving down teacher turnover and reducing the costs of hiring new staff each year. The costs of separation, recruitment, training and professional development can cost districts $18,000 or more per resignation, according to estimates from the Learning Policy Institute. The Mountain View Whisman School District, for example, has seen an annual exodus of more than 50 teachers in recent years, putting costs near an estimated $1 million.

“These are dollars that can be saved in better preparation upfront,” Fallon said.

The hope, Fallon said, is that the Sustainable Funding Project will get more schools and school districts to seriously consider investing in residencies — whether it’s modeled on Bullis or not — and that public schools in California have the means to support an in-house teacher training program.

“The hesitancy you most commonly see is the question of feasibility and affordability, and we think the money is available to move us in the right direction,” she said.

The Bullis Charter School (BCS) Board of Directors announced that Maureen Israel will be the new Superintendent of BCS, beginning with our 2020-2021 school year.

The Bullis Charter School (BCS) Board of Directors announced that Maureen Israel will be the new Superintendent of BCS, beginning with our 2020-2021 school year.